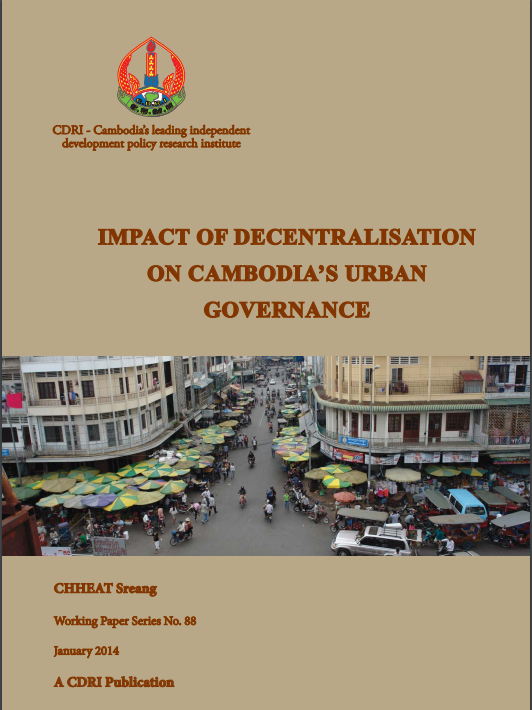

Impact of Decentralisation on Cambodia’s Urban Governance

Keyword: Urban governance, decentralisation reform, Sangkat councils, citizen participation, downward accountability

Abstract/Summary

This study explores the effects of decentralisation on urban governance in Cambodia, focusing on the role and performance of sangkats—the lowest administrative units in urban areas. While decentralisation has been promoted as a means to enhance local democracy, accountability, and service delivery, its implementation in urban contexts remains underexamined. Through qualitative fieldwork in Phnom Penh and six provincial towns, the study investigates sangkat councillors’ perceptions of citizen participation, downward accountability, and responsiveness. Findings reveal that urban sangkats face significant challenges due to limited financial and human resources, unclear functional mandates, and low civic engagement. Although Sangkats have contributed to small-scale infrastructure development, their ability to address urban issues such as sanitation, slum upgrading, and public services is constrained. Councillors often rely on political patronage and informal networks to mobilise resources. The study concludes that without clear authority and adequate resources, Sangkats struggle to fulfil their democratic and developmental roles. It recommends strengthening functional assignments, enhancing resource allocation, and developing innovative mechanisms to foster civic participation and accountability in urban governance.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.64202/wp.88.201401