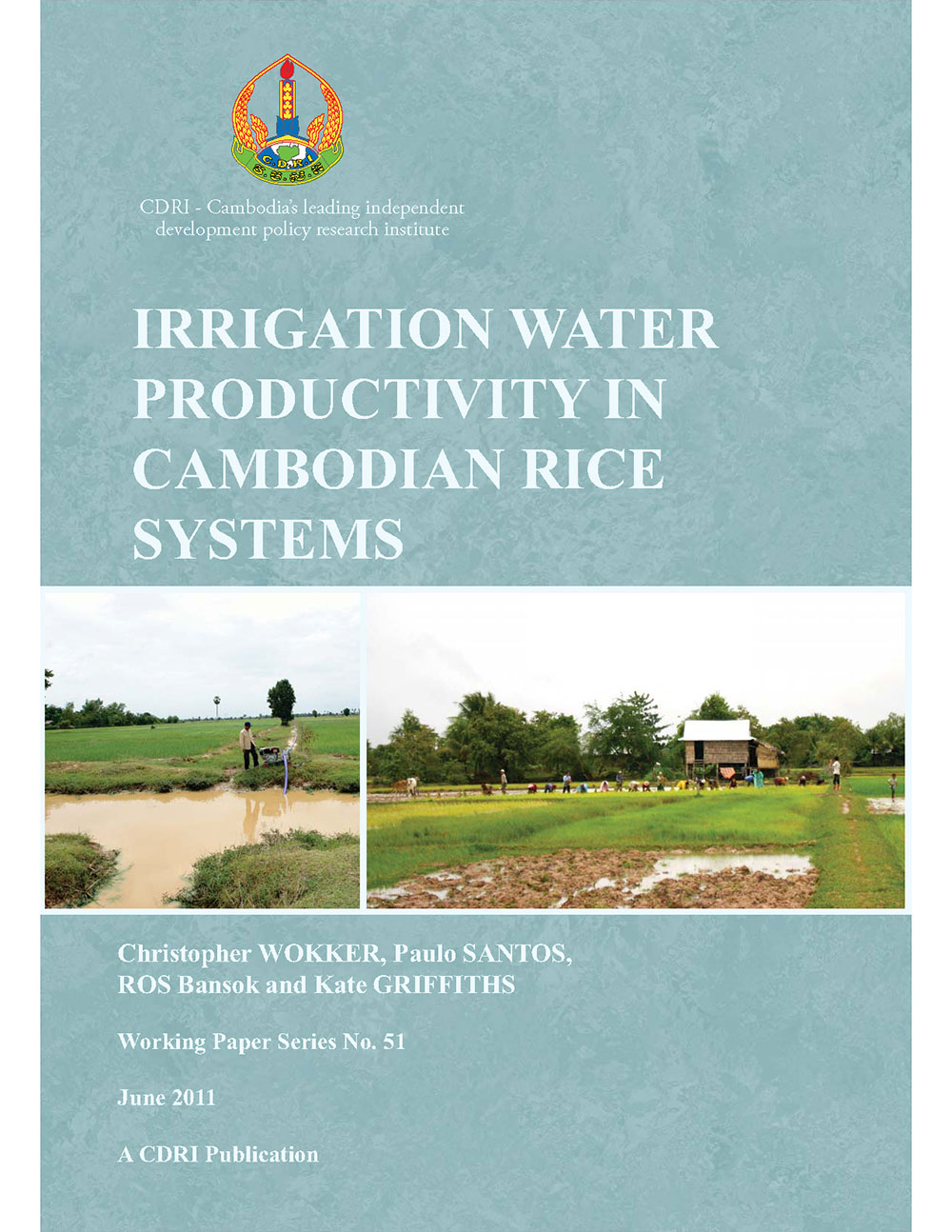

Irrigation Water Productivity in Cambodian Rice Systems

Keyword: Rice production, irrigation efficiency, water resource management, agricultural productivity, policy implications

Abstract/Summary

Cambodia’s economy is based largely on the agricultural sector

which contributes 33 percent of the national GDP and employs more than 67

percent of the national labour force. Rice production is central to this

sector: not only do the majority of Cambodia’s farmers depend directly and

indirectly on the success of the rice crop each year, but being the main food

staple, rice production is a significant factor in the national effort to

promote food security. Despite its importance, rice farming in Cambodia has

traditionally been dependent on rainfall rather than irrigation. Rainfall

distribution determines the success and size of the harvest and, as a result, farmers

generally only grow only one crop per year.

Recognising the importance of water management to promoting the

country’s rice production, the Royal Government of Cambodia and donors are

making efforts to expand the irrigated area in Cambodia. The expectation is

that irrigation will make farmers less reliant on rainfall, allowing them to

cultivate more crops with more certainty and predictability, resulting in

higher productivity and better livelihood outcomes. The government’s current

planning document emphasises the importance of water management to increase

agricultural productivity and stresses ‘rehabilitating and enhancing irrigation

potential’ (RGC 2009:28).

However, despite the importance given to irrigation in Cambodia’s

development strategies, there is lack of quantitative information regarding the

value of water at the farm level. This paper presents key findings from the

economic component of the Water Resources Management Research Capacity

Development Programme (WRMRCDP) to address this question and discusses some of

the policy implications of these findings, particularly in regard to the

definition of irrigation fees.

The key findings of this paper are that estimates of the extra

yield produced as a result of irrigation, when measured in terms of rice

production, are very low. This is particularly the case in the wet season: an

increase of 1 percent in the amount of water used leads to an increase in rice

yield of only 0.06 percent in the wet season and 0.12 percent in the dry

season. For amounts of water larger than 1000 cubic metres per plot, and

controlling for other inputs (including land), very little is added to yield

size.

The overall key policy implications are that:

- The marginal return from water use to farmers in the wet season is low; therefore, farmers will not be willing to pay much for water during the wet season;

- This lack of willingness to pay for water limits the feasibility of cost-recovery policies as well as decisions on infrastructure investment and maintenance;

- Increasing productivity in the wet season is central to any effort to better manage irrigation water.